Addressing Publisher Notes: Randomness

Shortly after the publication of our most recent blog post on Yargh, we submitted the game to a handful of publishers. While some publishers expressed admiration for the marketing package we had created and thought our game looked interesting, none asked for a playtest. When we asked for feedback, those that replied said that they felt the game seemed too random.

Around the same time, we had a number of playtests that went poorly. While previous playtests had ended with some playtesters saying this was one of their favorite games ever, this more recent set of playtests ended with playtesters frustrated because there was mathematically no way for them to win the game.

This section will be about how we made our game fairer and less random while preserving what made our game fun. (This post will assume you are familiar with the core mechanics of the game, which can be found here.)

Calming the Seas of Randomness

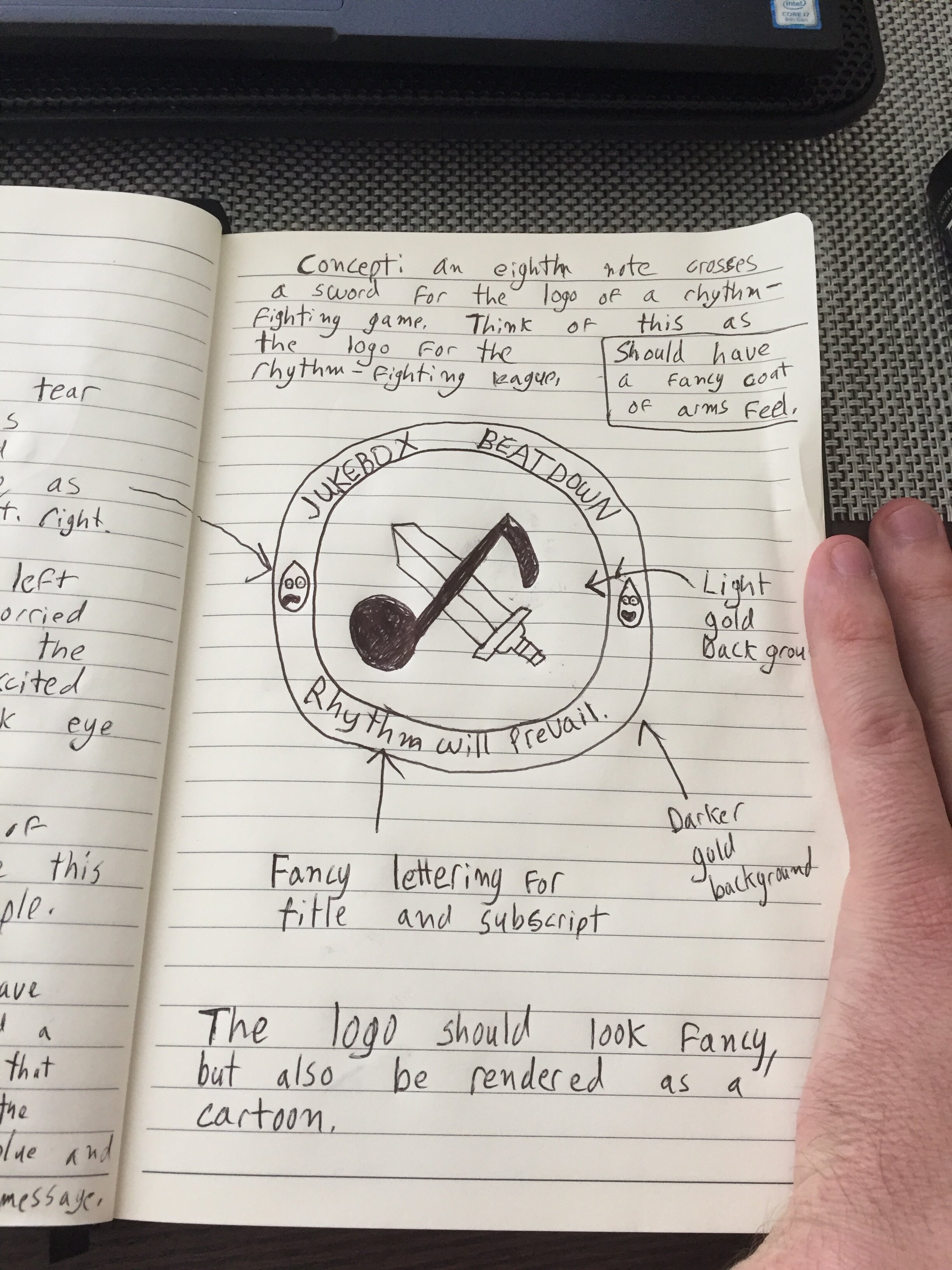

When pitching to publishers, there is the amount of randomness that appears to be in the game and there is the actual randomness that is in the game. When some publishers said they felt the game was too random, our initial reaction was that the game only seemed random because of our Chaos Dice, which were d6s with unique sets of faces like [0,1,5,10,15,20] or [8,8,8,16,16,16]. Given this, our instinct was to simply reduce the prevalence of these dice in our marketing materials.

But as we looked closer at our game, we realized that it actually had many sources of randomness.

Most glaringly, there was the problem of our Monsters. In a nutshell, they were designed in a way that created an experience that was sometimes too easy and sometimes too hard. During our Navigation phase, Players would choose between three randomly selected Monsters. Each Monster would have a level that would signify how difficult it was: 1 was easy, 2 was moderate, and 3 was hard. The Monster would have a Health value, Attack value, and targeting style, tuned in aggregate with their overall level. A Level 3 Monster, for example, might have high health and high attack while a Level 1 Monster had the opposite.

The problem with this approach is that our players’ power did not scale with the challenge the monsters were presenting. If the player drew 3 Level 3 Monsters, it was likely that they would die to the monster. If the player drew 3 Level 1 Monsters, the challenge the Monsters presented would be trivial. In addition, because level 1 Monsters gave less rewards, players who chose to fight them were less prepared for future rounds of play. This created a negative feedback loop where weak players stayed weak because they could only afford to challenge easy monsters.

Another problem was that the reward you got for beating each monster was proportional to how difficult they were. If the Player defeated a Level 3 Monster, they would get Power Cards, Artifacts, and a new Die. If they defeated a Level 1 Monster, they would only get Power cards.

An early draft of our loot table.

At first, Matt and I were at a loss as to how to solve this problem. It made sense to us that the more difficult Level 3 monsters would drop better loot and vice versa. But playtest after playtest showed us this made for an uneven experience.

To rethink how we could solve this problem, I read part of the excellent book Game Balance by Ian Schreiber and Brenda Romero. This book provided a useful vocabulary for talking about feedback loops and power-scaling. I learned a lot from this book but one of the most important lessons I gleaned was the importance of knowing the journey you want your players to go on. When we had first started working on Yargh, our focus had been on creating a game that spun up dramatic moments - what we had ignored (to our peril) was the journey that those moments were part of. We knew the scenes we wanted but we didn’t know the story. As a result, during some games, players would get weaker and weaker as the game progressed. During others, they would become far too powerful too early. It was hard to predict what experience the game would produce.

While searching for answers, we also took a closer look at how some of our inspirations handled the question of balance, namely Slay the Spire: The Board Game and Dicey Dungeons. We noticed that these games never took power permanently away from the player when the player faltered and that these games did not leave difficulty to chance. Both of these games had a small pool of enemies for the start of the game, another set for the mid-game, and a completely different set for the end-game. Revisiting these games made us rethink how we wanted to present monsters in Yargh.

Instead of each Monster having its own level, we decided that a Monster’s health would be determined by two factors: the round the players were in and the number of players.

To further simplify the Monsters, we also had the Monster’s attack scale with the round. This meant that the Monster would attack with 1d20 in round 1, 1d20 and 1d12 in round 2, and 2d20 in round 3. Therefore, the only thing unique to each monster was their name, picture, and special effect. This meant that each monster had a distinct flavor but was also presented roughly the same challenge to the player. Over the course of the game, the monsters would get progressively more difficult.

The table below lays out the stats for every monster in the game.

To match the monster’s gradual ramp up of power, we also changed how the player gained power. Instead of getting rewards based on how difficult the monster they killed was, players always got 1 die, two Power cards, and two Artifacts. This meant there was a linear relationship between how far the player had progressed in the game and how powerful they were. Combined with our ramping up of the Monster stats, these changes made for a game that was consistently moderately challenging because the player’s strength grew with the monster’s strength. We had struck the right balance of boredom and challenge. The winner of the monster-player battle was largely determined by skill.

Another major change that we made was changing how we handled player death. In early versions of the game, players would permanently lose 1 die or all their artifacts if they died. The problem with this approach is that it was too punishing. When a player lost a die, it was next to impossible for them to get back in the running for first place; dice were simply too important. For this reason, we introduced “Curse Cards”, which counted against a player’s score and temporarily disabled one of the player’s action card slots. Players would draw one of these cards when they died. This solution was punishing enough that players were scared of it but not so punishing that it doomed players.

Our original rules around death.

Players could dispel a curse card by placing dice that fit that card on top of it.

These changes were a huge improvement over the chaotic progression curve we previously had. One of the main insights we learned from these changes is that players should only get stronger during a game, never weaker.

We had removed the biggest source of our game’s randomness but there was still more work to do: we listed every element of our game that was affected by randomness and asked ourselves whether that randomness was Input Randomness or Output Randomness. In other words, we asked ourselves whether the randomness came into play before (input) or after (output) the player chose an action. We felt that having too much input randomness would make the game feel predetermined and too much output randomness would make it feel too chaotic.

We also identified situations where one player would be better off than their opponents due to luck as opposed to skill. For example, in an early iteration of the game, each player would draw 10 cards from a pile of 40 unique cards to make their starter deck. The problem with this approach is that one player could end up with a much stronger set of 10 cards than another player. To make the game more fair, we made it so that every player had the same set of 12 starting cards.

Our 12 starting cards.

The net result of these changes is that the game felt more fair: players felt that they won or lost due to their own skill as opposed to blind luck.

However, there was also the problem of how random the game looked to publishers. To address this issue, we revised our marketing materials to feature our Chaos dice far less prominently; we instead emphasized that the game was a crunchy but accessible, semi-cooperative experience.

Finding Balance

With all these changes, our game’s economy no longer made sense. As recommended by Game Balance, we began to calculate the elements of our game in terms of each other. For example, after some calculation, we knew that our dice were about as valuable to the player as two artifacts. Thinking this way enabled us to make more informed decisions about when to give which elements. Instead of increasing or decreasing elements of the game on gut feelings, we were able to intelligently determine how increasing one element may affect another element.

Designers we trusted had also raised concerns about the number of unique dice in our game; they said that manufacturing that number of unique dice would be prohibitively expensive. To reduce the perception of randomness in our game and address that concern, we lowered the amount of unique dice in our game from 20 to 10.

PAX Unplugged

With this new version of the game in place, Matt and I decided to attend PAX Unplugged, the enormous board game convention hosted in Philadelphia each year. We rented two tables from Unpub, the Unpublished Game Network, and playtested our game with PAX participants. The response to our game was generally positive - we had many positive comments about our core dice and card gameplay. On the other hand, some players were not a fan of the amount of reading in our game, especially during the Looting phase, where players haggled over 8 Artifact and Action cards. These players suggested that we use more icons and less text - which is a change we may do in the near future.

Our looting phase. Each Player gets two of these 8 cards.

One of the most valuable moments of the convention occurred during a talk called, “Take Your Damn Turn!”. The speaker, Rym DeCoster, explored the concept of a game’s “fun economy”, which he defined as the fun a game provides divided by its procedure or busywork. He proceeded to list examples of games that were fun but too “busy”; he discussed how Monopoly was hated by some despite being fun because it had a number of mechanics that lengthened the game arbitrarily. (In fairness, the original version of Monopoly was designed to show how capitalism sucked, not create a fun experience.)

This talk opened our eyes to the amount of procedure in our own game. As a result of this talk, we took several steps to reduce busywork, such as replacing a section where the players pick between 3 cards with a section where they simply draw 1 card. These small changes decreased the time of our game and subsequently increased our fun economy! That said, there are still some changes we need to make to streamline our game.

Lessons

What’s the future of Yargh? At this point, Matt and I have dedicated more than 50 playtests to the development of Yargh (which is not to mention all the work required to design the game in between those playtests.) While there are still improvements to be made, particularly around the streamlining of the game, we feel that most of the ideas we have left would ultimately result in a fundamentally different game. The game we have created is balanced, fun, and complete, so we are stopping development at this stage unless we receive notes from an interested publisher.

Yargh was a fun game to develop and it taught me a lot about game design. Here are some of the most salient points:

If you think your game is done playtesting, it’s not!

Once a board game has been sufficiently developed, any change to its design will have large ripple effects. Before making a change, ask yourself all the ways your change may alter player behavior. What strategies could become overpowered or underpowered? What new strategies might emerge? Will existing mechanics become more or less significant?

Randomness plus player agency can be fun. Randomness multiplied by randomness is chaos.

Your hook is the experience you create - not your components.

You will get far more critical playtest feedback from designers you don’t know than you will from friends. This is both a good and bad thing. Your game will be held to every scrutiny but that scrutiny is not always indicative of how the average person will perceive the game. Sometimes, other designers will give you the tough love you need. Sometimes, they will be clouded by their own version of what an ideal game is. In the latter case, ask yourself whether you and this other designer have the same values.

There are some mechanics that are considered “hardcore” and some that are considered “casual”. If you mix them too liberally, you may make a game that isn’t a great fit for either group.

A game is the median experience it creates, not the average. A balanced game is not an experience that is sometimes easy and sometimes hard. It’s a game that is consistently the right difficulty.

When you design your game, you should be able to articulate the journey you want your players to go on. For example, in Yargh, like many games, we wanted to increase the game’s complexity, difficulty, and power-fantasy for the player in an exponential fashion. For too much of Yargh’s development, we let randomness shape a large part of the player experience and we sometimes fooled ourselves into thinking the game was in a better place than it actually was when playtesters had a very fun experience.

You can learn more from your playtests by writing down the exact changes you’re testing and their observed effects. Matt and I would end every playtest by breaking down these observed effects and brainstorming solutions to new problems that had arisen. Those solutions then became our next set of changes.

You should be able to know roughly how far a player is into your game by looking at their playspace. If you cannot, the experience may be too loosely tuned.

Sometimes, that funny/cool/twisty card you love is the card that’s ruining the balance of your game.

Constantly ask yourself, “why would a player want to do that?” Break down their motivations mathematically. For every decision in the game, ask yourself if there is a dominant strategy that you have shaped.

I’m far from the first person to say this (which is true for all of these points), but if players need to use a turn guide throughout your entire game, it’s probably too complex for most players.