I am always trying to upgrade my software engineering skills so that I can design and produce more interesting games. Last month, I learned a tremendous amount from the seminal coding book Clean Code (which I covered in this blog post), so I thought I would next study Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Orientated Software, another software engineering classic.

I learned a huge amount from this book, so I wanted to share some interesting ideas from it. While many of the design patterns in the book have been discussed at length, not all of them have been discussed extensively in the context of game development. So, in this blog post, I will discuss how the Decorator and Bridge patterns can be used in game programming. My hope is that these examples will help readers recognize how these patterns can apply to their own projects. I’ll be using examples from popular games to illustrate these patterns, though I will be tweaking details to keep things simple.

Pattern: Decorator.

What it’s Generally Used For:

To add functionality to an object dynamically without changing the object itself. Decorators can “stack” onto each other, so you can add a theoretically infinite number of decorators to an object. In some cases, the order in which the decorator is applied to an object can create novel functionality.

One Potential Use in Games: Adding stackable attributes and behavior to in-game items.

Helpful Physical Metaphors: Russian Nesting Dolls, Onions.

Example: Borderlands and its procedurally generated weapons.

Games like Borderlands often boast that they effectively support an infinite number of unique weapons. In practice, these weapons are not totally unique but rather a set of base weapons (crossbows, shotguns, rocket launchers, etc.) that can be modified ad infinitum via a set of shared stats (reload rate, fire-damage, ice-damage, fire rate, etc.)

It is impractical for the game’s developers to create a combination of each base Weapon and set of stats, so they might use the Decorator pattern. What the decorator pattern allows the programmer to do is “wrap” a base object with additional functionality, like how a Russian nesting doll can be wrapped by another Russian nesting doll. When a Client (a program that sends a request to another program) needs some information from this nesting doll-like structure, it gets information from the outermost doll then moves onto the next smallest doll until it reaches the very smallest doll. When it reaches this base doll, it will return all the data it collected along the way to the Client.

For example, let’s say that in the new Borderlands there is a Shotgun, Rocket Launcher, and Crossbow that all inherit from the Weapon superclass. All Weapons share some basic stats (reload speed, fire-rate, damage, etc.) In our example, Player A finds a Fire Upgrade that adds Fire damage to a Shotgun in their inventory. If the Shotgun was programmed using the decorator pattern, this Fire Damage upgrade could be wrapped around the Shotgun base object.

A key point here is that the Shotgun class and the FireDamageUpgrade decorator inherit from the same Weapon superclass, so when a Client encounters the Fire Damage Decorator wrapped around the Shotgun (the client cannot access the Shotgun directly because the decorator is around it), it still treats the Decorator as a Weapon.

To use an onion metaphor, we do not consider a layer of an onion by itself to be a full onion, but we do treat a layer of onion on top of other layers to be an onion. A FireDamageUpgrade decorator by itself cannot function as a Weapon class, but when it is wrapped around a Shotgun class it is treated as a Weapon.

The strength of this pattern is its flexibility. In the Borderlands example above, the Decorator pattern allows me to:

Remove decorators I do not want (I can reverse the Fire Damage upgrade).

Easily add new functionality (I can add a Fire Damage upgrade on top of another Fire Damage upgrade.)

Create unique functionality through the order the decorators are wrapped (I can put a DamageMultiplier decorator that multiplies the effects of previous decorators.)

Implementation:

Pattern: Bridge Pattern.

What it’s Generally Used For: Allows two superclasses to evolve independently of each other yet still work together.

One Potential Use in Games: Matching AI personalities with NPC bodies that can express those personalities.

Helpful Physical Metaphor: Royal families and their subjects.

Example: Companions and their Fighting Styles in The Outer Worlds.

The Bridge pattern is very abstract, so I will first describe it in metaphorical terms.

Imagine there is a Royal family that rules over a group of Servants. The Servants are bound by an Oath that says they will Feed, Protect, and Entertain any member of the Royal family. Any Royal can call on any Servant to fulfill any part of the Oath. For example, a Royal King can call on any Servant Knight or Farmer to Entertain him.

What makes things interesting is that every servant has their own definition of fulfilling each part of the Oath. A Knight might Entertain a Royal by juggling swords, while a Farmer might Entertain a Royal by telling fables. A Jester might feed a Royal princess by gathering apples for her, while a Knight will feed the Princess by hunting a boar for her. The society functions (in its oppressive feudal way) like clockwork because every Servant can fulfill every part of the Oath and the Royals only command the Servants through the Oath.

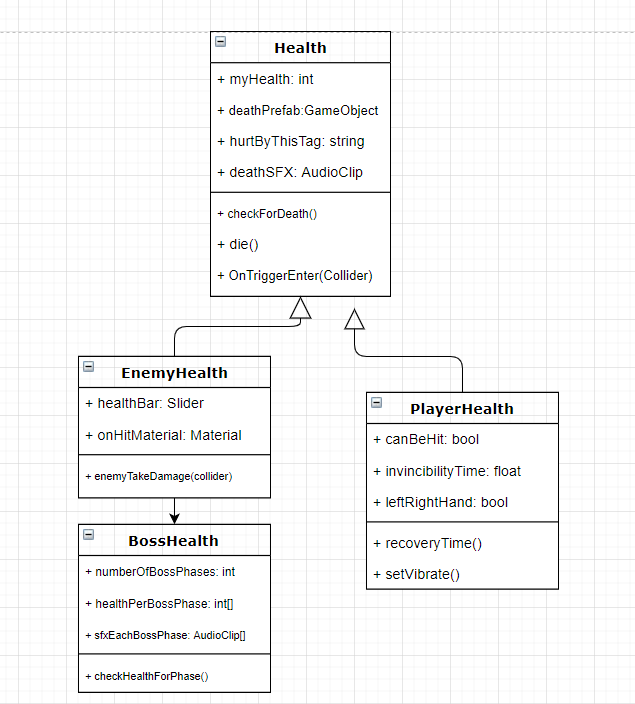

A UML diagram of this Royal / Servant society. Click on this image to see this diagram in more detail.

With this structure, Royals can ask for elaborate combinations of the Oath’s parts. A King, for example, can DemandFeast(), which can consist of four DemandEntertainmant() calls and 2 DemandFood() calls. A Prince can DemandCircus(), which comprises four DemandEntertainment() calls. Since every Servant can Entertain and Feed, the King’s Feast command can be carried out by any Servant.

The advantage of this structure is that as long as the Royals only ask for what is in the Oath and every Servant continues to fulfill the Oath, new Servants and Royals can enter the society without changing the behavior of existing Servants or Royals. For example, a new Servant Chef can join the society who Protects() by swinging a wooden spoon, Feeds() by cooking turkey, and Entertains() with parlor tricks. Since the Chef can Protect, Feed, and Entertain, he can serve any Royal. The Oath, in this metaphor, is the Bridge between the Royal superclass and the Servant superclass.

Imagine that the same society wanted to function without an Oath between Royals and Servants. Whenever a Royal asked a Servant to do something, they would need to check whether the Servant was capable of performing that task. If there were twenty Servants and twenty Royals, there would be 400 possible interactions between the groups to account for. That is a lot of room for error!

So how can this pattern be applied to game development?

One unconventional way the Bridge pattern could be used in Game Development is assigning Fighting Styles (AKA personalities) to Companion NPCs.

A Companion fighting an enemy in The Outer Worlds.

In The Outer Worlds, a sci-fi action-RPG, you spend a significant portion of the game with Companions that fight enemies alongside you. At any point in the game, you can ask this Companion to change their Fighting Style to either Aggressive, Defensive, or Passive. The Companions will use their loadout and unique combat ability to fulfill the Fighting Style you have chosen for them. So if you ask Parvati, the mechanic Companion, to act Aggressively, she will Shoot, Charge, and use her combat ability “Overload” to do so.

The stat sheet of Parvati, the first Companion most players will encounter.

For sake of simplicity, we’ll assume that all of the companions share a set of combat “primitives”, like Hide, Shoot, Charge, Heal, etc. A “Shoot” primitive may look different for every companion, but every companion is capable of fulfilling the “Shoot” request. Fighting Styles call on combinations of the primitives to create a semblance of a personality. A Passive fighting style might consist of mostly Healing and Hiding, while an Aggressive fighting style might consist of mostly Charging and Shooting.

The six Companions in Outer Worlds.

There are only six Companions and Three Fighting Styles in The Outer Worlds, so there are only eighteen possible combinations of Companions and Fighting Styles. It’s possible that Obsidian hard-coded each permutation of Fighting-Style and Companion (Aggressive-Parvati, Passive-Nyoka, Passive-Vicar Max, Defensive-Parvati, etc.) but they also may have used the Bridge pattern.

(In this context, the Fighting Style would be our Royal / Abstraction and the Companion would be our Servant / Implementer [Abstraction and Implementer being the formal names for those parts of the pattern.])

There would be many advantages to using the Bridge pattern in this situation. Let’s say Obsidian, the developer of Outer Worlds, wanted to add Morty from Rick and Morty as a Companion in a new DLC. If Morty inherited from the Companion subclass, Obsidian would not need to program an Aggressive-Morty, Passive-Morty, and Defensive-Morty. As long as Morty inherited from the Companion superclass, those permutations of Morty would automatically be available.

Aggressive-Morty.

The same would be true if Obsidian wanted to add a new Fighting Style. As long as the Fighting Style relied upon the Companion superclass’s methods, Obsidian would not need to create a new version of every Companion with that fighting style.

It’s important to note that just because any Companion can do something doesn’t mean that they do it well. For example, Obsidian could decide that when the Morty companion receives a command to Heal(), he cries and heals himself 0 points. While this may not be the best design, it is technically sound. Morty is fulfilling the Heal command - it’s just that his implementation of Heal doesn’t actually involve healing. The Bridge pattern ensures that Companions carries out requests from the Fighting Style. It doesn’t ensure that any Companion fulfills that request in a particular way.

A UML diagram of how Outer Worlds could implement the Bridge pattern. Click on this image to see this diagram in more detail.

Since the Bridge pattern allows Companions to create their own definition of fulfilling the Fighting Style’s requests, Obsidian has significant room to make creative choices. If they wanted to be very experimental, they could create a comically rebellious Companion that does the opposite of whatever you tell them to do. This character would Heal when you ask them to be Aggressive and Charge when you ask them to be Passive. To create a character like this, Obsidian would need to define Heal() as attacking and Shoot() as healing. This Rebel companion would still fulfill the Fighting Styles requests - they would Heal() when asked to Heal(). But like Morty, their version of Heal() would not include Healing. This is admittedly a silly example, but I think it underlines that Companions define how they execute the Fighting Style’s commands.

The Bridge pattern has other drawbacks as well. There’s a chance that a Fighting Style and a Companion may combine to create strange behavior. For example, imagine each of our companions has an Energy stat that they need to draw from to perform actions. The Morty Companion has 10 Energy by default and spends 3 energy to Shoot. If the Aggressive Fighting Style requires its Companion (Morty) to Shoot 4 times (requiring 12 energy) Morty cannot fulfill the Aggressive Fighting Style unless we consider his inability to Shoot a fourth time a successful execution of the Shoot command. When Companions manipulate variables that are outside the Bridge pattern as Morty did, there can be room for error.

This pattern doesn’t make sense in all cases. If each Companion in The Outer Worlds had a distinct, unchanging personality in combat, another pattern might be more appropriate. But since it has one superclass that relies heavily on another, a Bridge might be useful.

The Bridge Pattern has many strengths:

I can add, modify, or delete any Fighting Style or Companion without breaking anything.

I don’t have to handcraft an object that represents every combination of a Companion and an Fighting Style.

I can pair or unpair any Fighting Style and Companion during runtime.

Implementation Details:

Thanks for reading! If there are any other programming books that you recommend, please comment below!